The Cross of Burgundy (Spanish: Cruz de Borgoña, Cruz de San Andrés), a form of St. Andrew's cross, was first used in the 15th century as an emblem by the Valois Dukes of Burgundy, who ruled a large part of eastern Franceand the Low Countries as effectively an independent state. The Duchy of Burgundy was inherited by the House of Habsburg on the extinction of the Valois ducal line. The emblem was then assumed by the monarchs of Spain as a result of the Habsburgs bringing together, in the early 16th century, their Burgundian inheritance with the other extensive possessions they inherited throughout Europe and the Americas, including the crowns of Castile and Aragon, where the cross got a global impact, being found nowadays in different continents.

The Spanish monarchs continued to use it in their own arms after the Burgundian house was part of the Spanish Crown, and even after due to the extint of the burgundy house. From 1506 to 1701 it was used by Spain as a naval ensign, and up to 1843 as the land battle flag, and still appears on regimental colours, badges, shoulder patches and company guidons. The emblem also continues to be used in a variety of contexts in a number of European countries and in the Americas, reflecting both the extent of Valois Burgundy and the former Habsburg territories.

Burgundy

The banner strictly speaking dates back to the early 15th century, when the supporters of the Duke of Burgundy adopted the badge to show allegiance in the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War. It represents the cross on which Andrew the Apostle was crucified. The design is a red saltire resembling two crossed, roughly-pruned (knotted) branches, on a white field. In heraldic language, it may be blazoned argent, a saltire ragulée(or raguly) gules.

Pedro de Ayala, writing in the 1490s, claims it was first adopted by a previous Duke of Burgundy to honour his Scottish soldiers. This must be a reference to the Scottish soldiers recruited by John the Fearless in the first years of the fifteenth century, led by the Earl of Mar and Earl of Douglas.[original research?] However, earlier chronicle accounts and archaeological finds of heraldic badges from Paris indicate widespread adoption dates from 1411 in the context of factional warfare in the city and that its origins are more likely to relate to the fact that St. Andrew was the patron saint of the dukes of Burgundy[1]

Habsburgs and Spain

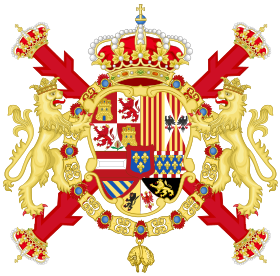

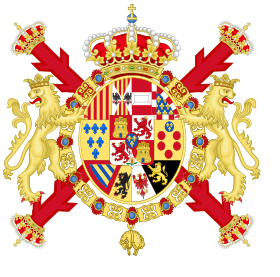

The year 1506 should be considered its theoretical earliest use in Spain (that is, it made appearance on the standards carried by Philip the Handsome's Burgundian life guards), although about 1525 might be perhaps a more likely estimate. Philip, after his marriage to Joanna of Castile, became the first Habsburg King of Spain and used the Cross of Burgundy as an emblem as it was the symbol of the house of his mother, Mary of Burgundy. From the time of Philip and Joanna's son, Emperor Charles V (King Charles I of Spain), different armies within his empire used the flag with the Cross of Burgundy over different fields. Nevertheless, the official field was still white. The Spanish monarchs – the Habsburgs and their successors' the House of Bourbon – continued to use the Cross of Burgundy in various forms, including as a supporter to the Royal Coat of Arms.[2] From the time of the Bourbon king Philip V (1700–1746), it seems that the Spanish naval ensign was white and bore a royal coat of arms in the centre, though it is said that the Burgundian flag was still flown as a jack ensign, that is, as a secondary flag, until Charles III introduced his new red-yellow-red naval ensign in 1785. It also remained in use in Spain's overseas empire (see #Overseas Empire of Spain below).

The flag eventually came to be adopted by the Carlists, a traditionalist-legitimist movement which fought three wars of succession against Isabella II of Spain, claiming the throne of Spain for Carlos, who would have been the legal heir under the Salic Law, which had been controversially abolished by Ferdinand VII. In the First Carlist War (1833–1840) the Burgundian banner, however, was a banner of the Regent Queen's standing Army rather than Carlist. After 1843 the red Burgundian saltire kept on appearing on the new brand red-yellow army flag under a four-quartered Castilian and Leonese coat of arms on the central yellow fess. Eventually, under the leadership of Manuel Fal Condé, the Cross of Burgundy became the Carlist badge in 1934.

Examples of use of the emblem

The Cross of Burgundy has appeared throughout its history, and continues to appear at present. Due to the impact of Spanish Empire as the first global powerhorse across the world, numerous flags and coats of arms of bodies, in various colours and in combination with other symbols can be found in old spanish domains. Users mostly have some direct or indirect relation to the historical Burgundy, though such connection can be very vague and lost in the mists of time. Most of them has direct link with Spanish Empire where this symbol got a global impact.

In Spain

- A Biscayan merchant ensign (inclusive of the so-called Consulate of Bilbao) (c. 1511–1830)

- A pre-1785 general Spanish merchant and privateering flag

- The Spanish Carlist Flag, from the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) up to the present

- The third co-official Flag of Spain during the Francoist regime (1939–1975)

- In Spain some local flags and coats of arms flaunt the cross of Burgundy in Guipúzcoa (Anzuola, etc.), Navarre (Tafalla, etc.), Aragón (Huesca and Lidón), Andalusia (Bujalance), Castile-La Mancha (Las Labores) and Catalonia (Creixell).

- A Basque Nationalist flag (for instance that of the Basque Alpinists in 1921–1978: Green Cross of Burgundy on white edged with red border)

- Nowadays, the Cross of Burgundy is still a symbol of the Spanish monarchy[3]

- A symbol painted on Spanish Air Force planes.[4] According to some scholars and aviation enthusiasts, however, the Spanish rudder marking (a black saltire on white) derives from the National Air Force deletion of the Republican Air Force red, yellow and purple flag, as a result of having lost some warplanes to friendly fire in the summer of 1936.[dubious ]

In France

- A French army colour

- Of the two line infantry regiments raised in the Franche-Comté of Burgundy: "Bourgogne" and "Royal-Comtois", both units raised in the late 17th century, together with the Household cavalry companies "Gendarmes Bourguignons" and "Chevaux Légers Bourguignons" and the Dijon, Autun, Vesoul and Salins provincial militia regiments

- In the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, the militian "gardes mobiles" from Dijon wore a red Burgundian saltire on their left cuff or shoulder)

- Continuing Burgundian and "Comtois" regionalism in France is keen on the Cross of Burgundy

- The coat of arms of Villers-Buzon (France) bears a sort of yellow or white Burgundian saltire on a wider red saltire

- The new region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté will use the Cross of Burgundy in its flag

In Belgium and the Austrian Netherlands

- The Austrian Netherlands' ensign in 1781–1786 was a black double-headed eagle on a red Burgundian saltire over a background of red over white over yellow

- As a Rexist Walloon Belgian Ultra-Right-wing flag and badge since 1940, including the Walloon Legion in German service on the Russian front, a unit eventually transferred to the Waffen-SS in 1943 (a red Cross of Burgundy, either on white or black)

- As the merchant ensign and badge of the Ostend Company (Austrian Netherlands) in 1717–1731

- The local flag and coat of arms of Philippeville (Belgium) bears a yellow Burgundian saltire on blue.

- The current Belgian naval ensign, which dates from 1950, may well be an homage to the cross of Burgundy

In the Netherlands

- The Military William Order, the foremost Dutch military decoration since 1815, bears a white Maltese cross and a green Burgundian saltire

- A similar style flag was used by the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands in the 15th and 16th centuries, which had been part of the Spanish Empire as well

- The flag of the Dutch municipality of Eijsden bears a red Burgundian saltire since 1966 (same for the municipal coat of arms or crest), also as an heritage of Burgundy, as a part of the Spanish Empire.

In South and Central America

During the Spanish colonization of the Americas the Cross of Burgundy served as the flag of the Viceroyalties of the New World (Bandera de Ultramar)[5] and as a recurrent symbol in the flags of the Spanish armed forces[6] and the Spanish Navy.[7] Nations that were once part of the Spanish Empire consider "las aspas de Borgoña" to be a historical flag, particularly appropriate for museum exhibits and the remains of the massive harbor-defense fortifications built in the 17th-18th centuries. At both San Juan National Historic Site in Puerto Rico, and at Castillo de San Marcos National Monument in St. Augustine, Florida, the Cross of Burgundy is daily flown over the historic forts, built by Spain to defend their lines of communication between the territories of their New World empire. The flying of this flag reminds people today of the impact Spain and its military had on world history for over 400 years. It was also used by Spanish military forces.

- In present-day Bolivia the Cross of Burgundy (which is represented with a golden crown in the center) is the official flag of the department of Chuquisaca.

- The Flag of Valdivia, which is composed of a red saltire on a white field is thought to have originated from the Spanish Cross of Burgundy, as the city of Valdivia in southern Chile was a very important stronghold of the Spanish Empire.

In the United States[edit]

- The flag of Alabama and flag of Florida each include a plain red saltire, partly to recognize the colonial period when the Spanish Cross of Burgundy was used.

- The Cross of Burgundy is still flown over Fort San Cristobal and Fort San Felipe del Morro, both of which are former Spanish fortifications located in San Juan, Puerto Rico, as well as the Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine, Florida.

Gallery

|  |

Common Version of the Standard Colours (1700-1761)[2] | Common Version of the Standard Colours (1761-1843)[2] |

(1843-1868/1874-1931) Variant with the lesser royal arms quarters[2] | (1871/1873) Reign of King Amadeo[2] | (1874-1931) Variant with the national quarters[2] |

See also

References

- ^ Hutchinson, Emily (2007). "Partisan identity in the French civil war,1405–1418: reconsidering the evidence on liverybadges". Journal of Medieval History. 33 (3): 250–274. doi:10.1016/j.jmedhist.2007.07.006.

- ^ a b c d e f *Álvarez Abeilhé, Juan. La bandera de España. El origen militar de los símbolos de España. Revista de historia militar Año LIV (2010). Núm extraord. Madrid: Ministerio de Defensa. ISSN 0482-5748. PP. 37-69.

- ^ Royal Spanish Household website Archived July 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Spanish Air Force Website Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Luis Tinajero Portes (1994), Días Conmemorativos en la Historia de México, Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, p. 39, ISBN 9789686194654,

(...) atravesado diagonalmente por dos brazos que formaba la cruz de San Andrés, también de seda y de color morado. (...) Este estandarte virreinal duró como símbolo de la Nueva España hasta el ya citado 24 de agosto de 1821 (...) Translation: (...) Crossed diagonally by two arms forming the cross of St. Andrew, also of silk and purple. (...) This viceroyal banner lasted as a symbol of colonial New Spain to the aforementioned 24 August 1821 (...) "

- ^ Escudo, Ministerio de Defensa. Unidad Militar de Emergencias.,

Para darle el carácter militar al escudo se coloca en la parte posterior (acolada), la Cruz de Borgoña (aspas), que es el símbolo militar de más antiguedad y tradición en las Fuerzas Armadas españolas.

- ^ Historia de la Armada, Ministerio de Defensa. Armada Española

- ^ Flags of the World (ed.):The Burgundy cross,... used by Spain, especially at sea, for many years. In much more recent times, it was a symbol of Carlism (Requetés) during the Spanish Civil War and afterwards, and by the Traditionalist Party (Partido Tradicionalista) during the post-Franco years crwflags.com google.es